One of the reasons, I believe, that the teaching of history has become so controversial, is that roughly since World War II, the history profession has dedicated itself to the kind of empirical, evidence-based search, that undermines myth.įor example, Nancy Isenberg’s 2016 book, "White Trash: The 400-year Untold History of Class in America," essentially seeks to undo perhaps the most important American myth of all, that of the Protestant Work Ethic, the Horatio Alger myth, the myth of equality of opportunity, or whatever you choose to call it. One of the traditional purposes of the historian, at least up to the last 60 years or so, was to try to create accepted narrative patterns out of the well-founded belief that cultures cannot survive without them.Īnother term, I suppose, is cultural myth. But in my experience the course of history is as often settled by someone’s having a belly-ache, or not sleeping well, or a sailor getting drunk, or some aristocratic harlot waggling her backside." Policies, they say, and the subtly laid schemes of statesmen, are what influence the destinies of nations the opinions of intellectuals, the writings of philosophers, settle the fate of mankind…. That is another story, which I shall set down in its proper place… but I mention it here because it shows how great events are decided by trifles.

"If I had been the hero everyone thought I was, or even a half decent soldier, Lee would have won the battle of Gettysburg, and probably captured Washington.

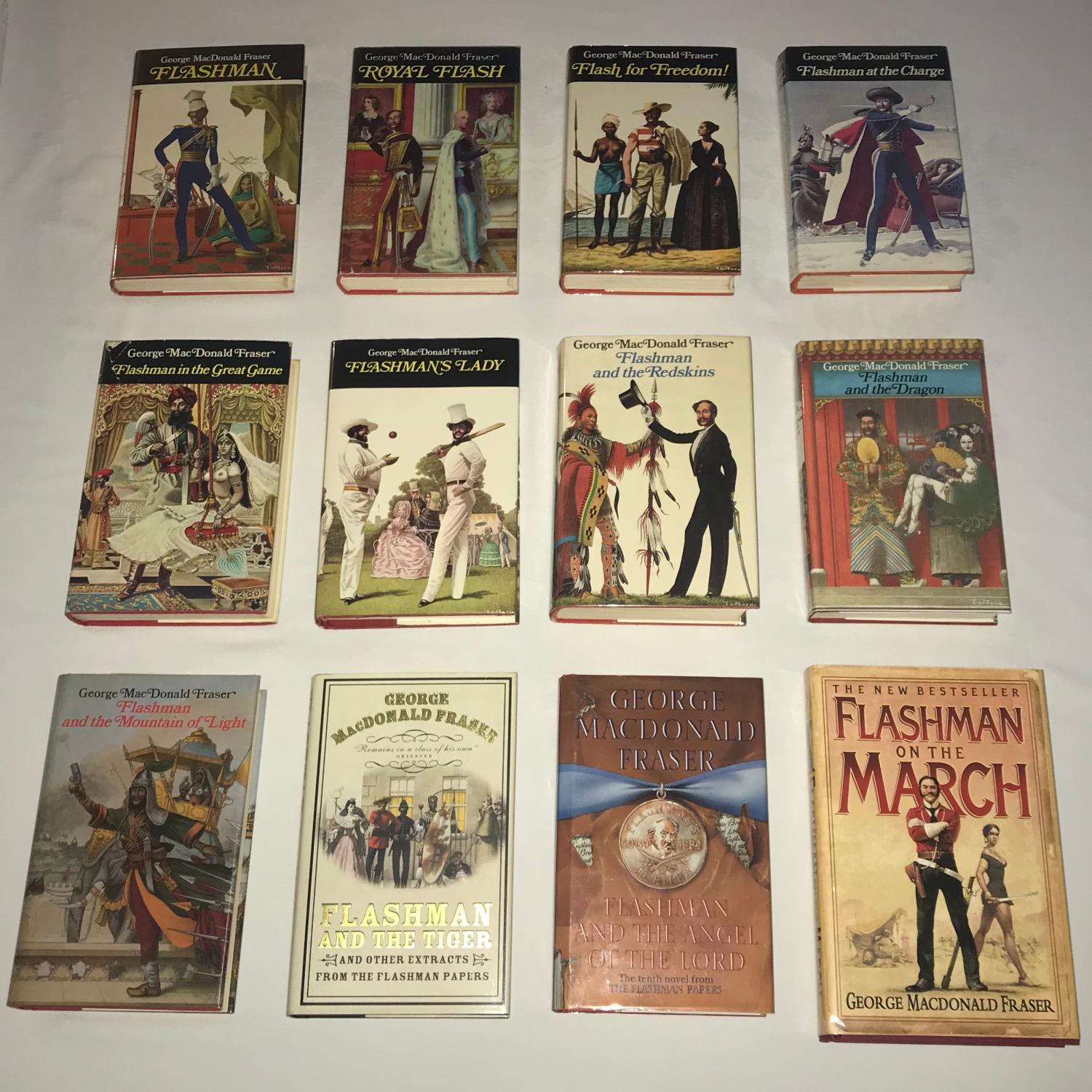

He said something in the opening of the series’ second book, "Royal Flash," that I absolutely agree with to this day, and which places us both far outside the mainstream of current poststructural historical practice: In the process of the 12 novels, Fraser had a lot to say about the contingencies of history, and how little we really know.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)